Psilocybin Microdosing Explained: How It Works and What to Know

Interest in psilocybin microdosing has surged in recent years, fuelled by personal stories and a broader shift towards self-directed mental well-being. But separating curiosity from credible information matters, especially with psychedelics.1

Contents:

- Quick summary

- What is psilocybin microdosing?

- Psilocybin truffles vs mushrooms: what’s the difference?

- How does psilocybin microdosing work?

- What does psilocybin microdosing feel like?

- Potential benefits: What does the research say?

- Is psilocybin microdosing safe?

- Is psilocybin microdosing legal?

- What we know so far about psilocybin microdosing

- Safety & Legal Note

- References

In simple terms, psilocybin microdosing refers to taking very small, sub-perceptual amounts of psilocybin (the primary psychoactive compound in “magic mushrooms” and "magic truffles") on a repeating schedule, with the aim of subtle day-to-day effects rather than a full psychedelic experience. If you’ve been wondering what psilocybin microdosing is, this guide sets out the basics in plain language.

What is psilocybin microdosing?

Psilocybin is a naturally occurring compound found in certain mushrooms. In the body, it is converted to psilocin, which interacts with serotonin receptors in the brain and can alter perception, emotion, and thought patterns at higher doses.2

What is psilocybin microdosing? It’s the practice of taking a very small amount, typically low enough to avoid noticeable psychedelic effects, on an intermittent schedule. Compared with a full psychedelic dose (where changes to perception and sense of self may be pronounced for several hours), microdosing aims for subtle, day-to-day shifts without intoxication.

So, what qualifies as a microdose? There’s no universally accepted standard, but it’s commonly described as a fraction of a typical recreational or ceremonial dose, adjusted for the individual and the preparation.

People who microdose often report goals such as improved focus, steadier mood, or greater creativity. It’s important to separate these anecdotal accounts from clinical research, which is still emerging and does not yet provide definitive conclusions about benefits, risks, or best practices.3

Psilocybin truffles vs mushrooms: what’s the difference?

People often say “magic mushrooms” as a catch-all, but in the Netherlands, the legal retail reality is usually psilocybin truffles. Truffles are not a different drug; they’re a different part of the fungus. Specifically, they’re sclerotia, dense underground growths some psilocybin-producing species form.

From a practical standpoint, the experience is still “psilocybin”, but the key differences are about format, storage, consistency, and legal status (which is highly location-dependent).

Why pre-dosed truffle packs are common (and what that changes)

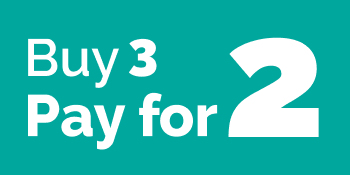

One of the biggest real-world problems with microdosing is simple: measurement and consistency. With loose material, people can easily take more than intended, especially when potency varies between batches.

Pre-dosed truffle microdosing packs are designed to reduce that risk by standardising the amount per serving. This can improve consistency for users who want to track subtle patterns over time—because it removes a common variable: imprecise measuring.

Important nuance: “pre-dosed” can reduce guesswork, but it doesn’t guarantee identical effects for every person. Sleep, stress, food intake, caffeine, mindset, and personal sensitivity still strongly shape outcomes.

How does microdosing psilocybin differ from taking full psychedelic doses?

Although the same compound is involved, a microdose and a full psychedelic dose are intended to produce very different experiences.

With a full dose, psilocybin typically causes clear, time-limited alterations in perception and cognition. People may notice vivid visual changes, shifts in time perception, heightened emotions, and a different sense of self or “ego” for several hours. Because these effects can be intense and unpredictable, a full dose is usually approached as a planned event rather than something fitted around ordinary responsibilities.

A microdose, by contrast, is generally taken with the expectation that daily functioning remains largely unchanged. The aim is not to “trip”, but to take an amount that sits below the threshold of obvious psychedelic effects. In practical terms, someone microdosing would expect to be able to work, socialise, and complete routine tasks without marked impairment.

The difference in purpose is just as important as the difference in effects. Full-dose use is often framed around introspection, emotional processing, spiritual exploration, or a deliberately immersive experience. Microdosing is more commonly framed as a subtle wellness-style routine, something people hope might support a steadier mood, concentration, or creativity over time.

It’s worth noting that these goals are largely based on self-reports rather than definitive clinical evidence. Individual sensitivity, expectations, and context can shape the experience at any dose. Even at lower amounts, some people report feeling more emotionally open, mildly restless, or distracted, while others notice very little.

Another key distinction is how risks tend to show up. At full doses, the main short-term concerns relate to acute psychological effects (for example, anxiety or confusion), judgment, and the need for a safe setting. With microdosing, concerns more often centre on repetition and consistency: dosing too high, using it too frequently, not accounting for interactions with other substances, or assuming that “sub-perceptual” automatically means “risk-free”.4

In other words, microdosing is best understood as a different use case rather than a lighter version of a full psychedelic session. The intent is subtlety and continuity, while full dosing is about a pronounced, time-bound alteration in consciousness.

Psilocybin microdosing dosage: What people mean by a “microdose”

When people discuss microdosing, they usually mean sub-perceptual dosing, an amount intended to sit below the level that produces obvious psychedelic effects, such as visual changes or a markedly altered sense of self. The idea is subtlety, not intoxication.

However, there is no single, agreed standard for what counts as a microdose. Sensitivity can vary widely between individuals, and the potency of mushroom material can be inconsistent. Even the same person may respond differently depending on factors such as sleep, stress, food intake, and other substances.

Psilocybin microdosing dosage explained, at a high level, is less about a specific number and more about the intended threshold: low enough to support normal daily activities, yet noticeable enough, for some, to feel like a gentle shift. This lack of standardisation is one reason research findings and real-world reports can be difficult to compare.3

How does psilocybin microdosing work?

To understand how psilocybin microdosing works, it helps to start with what psilocybin does in the body. Psilocybin is converted into psilocin, which can bind to several serotonin receptors, chemical “docking sites” involved in mood, perception, and cognition.2

The receptor most often discussed is 5-HT2A. At higher doses, strong stimulation of 5-HT2A is linked with the characteristic psychedelic effects, including altered perception and changes in the way different brain networks communicate. With microdosing, the same pathways may be engaged more subtly, though the exact relationship between dose and brain effects is still being mapped.

Some researchers have proposed that repeated low-level stimulation could influence neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to form and reorganise connections, which might, in theory, affect habits, learning, or emotional flexibility. Others point to potential shifts in attention and “top-down” filtering, which could change how we interpret everyday experiences.

Crucially, these mechanisms are still being studied, and microdosing-specific evidence remains limited. Early findings are mixed, and separating true pharmacological effects from expectation and context continues to be a challenge in current research.5

How does psilocybin microdosing work in the brain?

When scientists explore how psilocybin microdosing works in the brain, they often focus on large-scale brain networks, groups of regions that coordinate activity. One of the best-known is the default mode network (DMN), which is associated with self-referential thinking, mind-wandering, and internal narrative.

In full psychedelic doses, imaging studies suggest psilocybin can temporarily reduce the usual tight organisation of networks like the DMN and increase cross-talk between areas that don’t normally communicate as much. This is one proposed reason for pronounced changes in perception and sense of self.

With microdoses, any changes are expected to be far smaller. The amount of psilocin reaching the brain may be enough to lightly influence signalling, but not enough to produce overt perceptual shifts, so effects may feel subtle, inconsistent, or even imperceptible.

Emerging neuroscience research is beginning to investigate microdosing specifically, but the evidence base remains early. For now, any claims about precise network-level changes should be treated as provisional rather than settled science.5

What does psilocybin microdosing feel like?

What does psilocybin microdosing feel like? Most descriptions centre on subtle, everyday shifts rather than dramatic psychedelic effects. People who choose to microdose sometimes report feeling a touch more focused, mentally “clear”, or more aware of their mood and emotional patterns.

Just as commonly, people report little to no noticeable change. That can be because the dose is deliberately kept below an obvious threshold, because individual sensitivity varies, or because day-to-day factors such as sleep, stress, caffeine, and food make small differences hard to detect.

Placebo and expectation effects also matter. If someone strongly believes microdosing will improve productivity or well-being, they may pay closer attention to positive moments and interpret normal fluctuations as meaningful. This is one reason why blinded studies are important, and why early research has produced mixed results.1

Overall, if effects are present, they’re usually described as gentle and inconsistent rather than intense or guaranteed.

Potential benefits: What does the research say?

Interest in microdosing is often driven by hopes of feeling more balanced day to day, whether that’s a steadier mood, clearer thinking, or a small boost in creativity.

When it comes to psilocybin microdosing benefits, the scientific picture remains mixed and inconclusive. Anecdotally, some people report improvements in well-being, focus, and emotional resilience. However, controlled and blinded studies have often found smaller effects than expected, with results that can be difficult to separate from placebo and expectation.1

Psilocybin microdosing and mental health

A major reason people look into psilocybin microdosing for mental health is curiosity around anxiety, low mood, and general well-being. Most of the clinical excitement around psilocybin so far has come from supervised, full-dose therapy research, not from microdosing.

Microdosing studies that measure mental health outcomes are still limited, and results have been inconsistent. Some surveys and self-reports suggest perceived improvements, but these can be influenced by expectation, lifestyle changes, or other confounding factors that controlled trials try to minimise.3

It’s also important to be clear: microdosing is not a clinically approved treatment for depression or anxiety, and this information is not medical advice. If you’re struggling with your mental health, the safest step is to speak with a qualified healthcare professional who can offer appropriate support and guidance.

Is psilocybin microdosing safe?

Is psilocybin microdosing safe? Research is still developing, so there isn’t a simple, universal answer. While microdoses are intended to be sub-perceptual, potential risks remain, such as anxiety, irritability, sleep disruption, or feeling emotionally raw, particularly in psychologically sensitive people.4

Contraindications also matter. In research settings, participants are typically screened for a personal or family history of psychosis or bipolar disorder, as well as for medications or conditions that could increase risk. This screening is one reason study outcomes may not translate neatly to real-world, unsupervised use.

A further concern is what we don’t yet know. Long-term data on repeated microdosing is limited, and questions remain around mental health impacts over time and the effects of varying potency or mis-measured doses. If you’re considering microdosing, it’s wise to speak with a qualified healthcare professional.

Is psilocybin microdosing legal?

Is psilocybin microdosing legal? In many countries, psilocybin is a controlled substance, which means possessing, buying, or supplying it, even in very small amounts, may be illegal. Laws also differ widely between regions, and enforcement can vary, so it’s important not to assume that “micro” automatically means permissible.

There are a few notable exceptions and grey areas. For example, in the Netherlands, psilocybin-containing truffles have historically been sold through licensed shops, while psilocybin mushrooms are prohibited. Even then, rules can change, and products may fall under different regulations depending on form and intended use.

Because the legal landscape is complex and evolves quickly, the safest approach is to check your local laws and official government guidance before making any decisions. If you’re unsure, seek advice from a qualified legal professional in your jurisdiction.

What we know so far about psilocybin microdosing

So far, the most reliable conclusion is that microdosing is widely discussed, but not yet well understood. Some people describe subtle shifts in mood, focus, or self-awareness, while others notice little at all, making it difficult to separate genuine effects from expectation and lifestyle factors.

At the same time, early research has produced mixed findings, and there’s limited long-term data on repeated use. That uncertainty is exactly why responsible, informed curiosity matters.

References

- Szigeti B, Kartner L, Blemings A, et al. Self-blinding citizen science to explore psychedelic microdosing. Baker CI, Shackman A, Perez Garcia-Romeu A, Hutten N, eds. eLife. 2021;10:e62878. doi:https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62878 ↩︎

- Nichols DE. Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews. 2016;68(2):264-355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478 ↩︎

- Polito V, Stevenson RJ. A systematic study of microdosing psychedelics. Arnone D, ed. PLOS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0211023. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211023 ↩︎

- Johnson M, Richards W, Griffiths R. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2008;22(6):603-620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881108093587 ↩︎

- Cameron LP, Tombari RJ, Lu J, et al. A non-hallucinogenic psychedelic analogue with therapeutic potential. Nature. 2020;589. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-3008-z ↩︎