What You Need to Know About CBN

CBN is one of the dozens of hemp-derived cannabinoids currently being explored by researchers. Keep reading to find out the key attributes of CBN, a mildly psychoactive cannabinoid that only exists because of THC.

Contents:

What is CBN?

Though classed as a minor cannabinoid, cannabinol (CBN) may prove a potent addition to wellness products. Thanks to increased research on the cannabinoid’s effects, we’re closer to determining if CBN has a beneficial effect on processes such as sleep and appetite.

However, isolating and utilising CBN is not without several challenges. First, as mentioned, cannabinol is considered a “minor” cannabinoid—that’s because it naturally appears in low concentrations in live cannabis plants, especially compared to CBD or THC. And this brings us to the second major challenge; CBN is actually a derivative of THC, which, as you can imagine, has the potential to cause some issues with legality.

Although, rather interestingly, CBN was one of the first cannabinoids discovered in the 1800s, it wasn't until the 1930s that scientists determined its chemical structure.[1]

You see, not all cannabinoids exist in the same ratio or at the same time. For example, cannabinoids slowly transform into different compounds when exposed to light, air, or heat. This is especially true for CBN, which is created as THC oxidises. As such, in order to harness naturally high levels of CBN, you need to use mature hemp plants or aged plant material.

What's the difference between CBN and CBD?

The most significant difference between CBN and CBD is how the two cannabinoids are created. As we've alluded to, CBN is what THC breaks down into with age and exposure to the elements. CBD, on the other hand, exists on its own separate branch of the cannabinoid family tree. Given its relative abundance in modern cultivars of hemp and cannabis, CBD is considered a “major” cannabinoid to CBN’s “minor” status.

The difference in chemical structure also influences how CBD and CBN interact with the endocannabinoid system (ECS). While CBD acts as a kind of general manager of the ECS, CBN shows a more distinct affinity for receptors in the body linked to sleep, mood, and appetite.[2]

Moreover, CBN is deemed to be slightly psychoactive, especially in higher doses. This is a sensitive issue, as the cannabinoid is not intoxicating in the way of THC—but it is not necessarily devoid of mental effects either. CBD is generally thought to not induce any psychoactive effects, although this too is contested. Given their overall effects, however, both cannabinoids are often taken as wellness supplements, without significantly affecting one’s consciousness.

When you also consider the potential benefits of the entourage effect, a phenomenon that posits the profound influence of cannabis compounds working together, CBN and CBD both feature a wealth of potential.

Will CBN make you fail a drug test?

Considering CBN's relationship with THC, it makes sense to question the former’s potential to make you fail a drug test. By and large, CBN is not included in the list of drugs for which workplace tests screen. That said, as it derives from THC, there is a small chance of CBN flagging a false positive on a drug test.

Carefully formulated CBN products made from hemp shouldn't cause you any trouble on a drug test. If, however, the CBN product is a derivative of cannabis plant material (i.e. marijuana), the risk of THC levels being above the legal threshold is significantly greater.

How does CBN work?

To understand how cannabinoids such as CBN influence key biological functions, we need to take a look at the ECS. This regulatory system exists to maintain a balance between areas such as our immune, digestive, and central nervous systems.

The ECS performs this task primarily through a network of CB1 and CB2 receptors, with each receptor group activated by specific chemical compounds. For example, when a cannabinoid binds to a receptor attached to cells in the immune system, it has the potential to trigger various biological changes.

This, albeit simplified, role of the ECS is how all cannabinoids interact with the human body—CBN included. However, in the case of cannabinol specifically, it appears to bind mainly to CB2 receptors, of which most exist in the immune system and peripheral organs.

CBN and the endocannabinoid system

In addition to CB2 receptors, evidence from test tube studies suggests CBN may also influence TRP channels, a group of receptors broadly linked with sensations such as pain, temperature, and taste.[3]

Fortunately, CBN's lack of affinity for CB1 receptors prevents the molecule from inducing notable psychotropic side effects. However, as is often the case with minor cannabinoids like CBN, we still don't fully understand the cannabinoid's mechanisms of action or scope of effects.

What are the effects of CBN?

While preclinical studies suggest a handful of interactions, the challenge of isolating significant quantities of CBN has prevented more extensive studies from taking place. Although early indications appear positive, larger, more comprehensive trials are needed.

CBN and appetite

Although the appetite-stimulating qualities of THC are well-documented, the downside is that the compound induces psychotropic side effects. This led the University of Reading to test whether cannabinol (alongside CBD and CBG) could influence appetite without unwanted side effects.[4]

During the study, CBN and CBD showed an interesting influence on "appetitive behaviours", while CBG induced "no changes". Researchers concluded that cannabinol might, in the future, provide an alternative to THC.

CBN and inflammation

A comprehensive review published in the FASEB Journal examined the effect of numerous compounds within Cannabis sativa. Of the twelve reviewed, CBN showed a promising relationship with chronic inflammation.[5]

Additionally, the review concluded that the compounds were "generally free from adverse effects". However, the researchers noted that the mechanism of action differed from traditional NSAIDs used for inflammation, and further investigation was warranted.

CBN and sleep

While anecdotes have previously touted CBN as a potential sleep aid, a review from American researchers has cast doubt on those claims.[6] However, that doesn't mean CBN has little or no influence on sleep. Instead, it means that the complexity of the relationship between the endocannabinoid system and CBN warrants further investigation.

As the 2021 study rightly points out, "randomised controlled trials are needed", and "these studies should specifically evaluate the effects on sleep" through validated sleep questionnaires. The positive aspect of CBN, however, is that it appears to exhibit few unwanted side effects, making its influence on sleep a worthwhile attribute to explore.

CBN products

Despite the difficulty of isolating significant quantities of CBN, it is still possible. Not only are there several CBN-focused products available, but many CBD oils, capsules, and supplements also make use of cannabinol for more well-rounded effects.

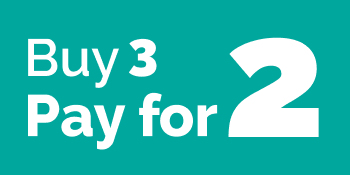

• CBN oils: These oils harness the influence of CBN alongside mild concentrations of CBD to influence well-being from multiple angles. The dosing regime for CBN oils is similar to that of CBD-focused products. Taking 3–4 drops up to 3 times a day is a great way for most people to get familiar with CBN.

• Complete Sleep: This sophisticated blend of CBD, CBN, chamomile, and lavender may help to support naturally soothing sleep. A significant benefit of CBN is its synergy with other natural ingredients linked to sleep and sleep quality. Blending these compounds into a simple, long-term supplement, Complete Sleep is ideal for users looking to test the properties of CBN for themselves.

• Stay Asleep Capsules: These handy capsules also play to CBN's synergy with natural ingredients. Working alongside CBD, hops, and 5-HTP, this unique formula offers an all-natural sleep experience. Given the importance of restful sleep to mental and physical well-being, supplements that incorporate multiple cannabinoids could prove crucial for many individuals.

CBN: A minor cannabinoid with a potentially major role in well-being

Despite CBN's elusive nature, there's no doubt that this minor cannabinoid shows some potential in the realms of sleep, inflammation, and appetite. The key, of course, is pushing for more placebo-controlled human trials on CBN’s effects in isolation, and when combined with other natural ingredients.

To explore the diverse impact of CBN oils, Complete Sleep, and Stay Asleep Capsules, visit the Cibdol store. And to learn more about the roles of major and minor cannabinoids in well-being, check out our CBD Encyclopedia for everything you need to know.

FAQ

- Is CBN legal?

- CBN isn't a scheduled substance; however, as it derives from THC, laws and restrictions on CBN may differ at a local level.

- What is CBN oil?

- CBN oil contains CBN alongside CBD, terpenes, and olive oil to provide a diverse influence on well-being.

- Is CBN psychoactive?

- CBN is considered mildly psychoactive in larger doses, and is not considered to cause a “high”.

[1] Pertwee RG. Cannabinoid pharmacology: The first 66 years - PMC. Cannabinoid pharmacology: the first 66 years. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1760722/. Published 2006. Accessed April 25, 2022. [Source]

[2] Cannabinol. Cannabinol - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/cannabinol. Accessed April 25, 2022. [Source]

[3] De Petrocellis L, Ligresti A, Moriello AS, et al. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. British journal of pharmacology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3165957/. Published August 2011. Accessed April 25, 2022. [Source]

[4] Farrimond JA, Whalley BJ, Williams CM. Cannabinol and cannabidiol exert opposing effects on rat feeding patterns - psychopharmacology. SpringerLink. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00213-012-2697-x. Published April 28, 2012. Accessed April 25, 2022. [Source]

[5] SH; ZRBB. Cannabinoids, inflammation, and fibrosis. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27435265/. Published 2016. Accessed April 25, 2022. [Source]

[6] J; C. Cannabinol and sleep: Separating fact from fiction. Cannabis and cannabinoid research. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34468204/. Published 2021. Accessed April 25, 2022. [Source]